galeria marcelo guarnieri | rio de janeiro

abertura/opening

13.08.2016 / 11h – 17h

August 13, 2016 / 11am – 5pm

período de visitação/exhibition

13.08 – 17.09.2016

Rua Teixeira de Melo, 31 – lojas C/D

Ipanema – Rio de Janeiro – Brasil

[ mapa/map ]

Luiz Paulo Baravelli

por Agnaldo Farias

É de Matisse um ensinamento essencial sobre a natureza do desenho: o primeiro risco numa folha de papel é na verdade o quinto. Poucos se dão conta que as bordas de uma obra de arte são parte dela. Que o trabalho começa no momento em que o artista se debruça sobre o material, mais ou menos como se dá com os jogadores de futebol que antes mesmo do jogo começar, no momento em que cantam o hino, não estão só cantando, já estão jogando. Luiz Paulo Baravelli, desde sempre fiel ao princípio de desafiar os limites, começa cada trabalho dessa série de cabeças desenhando com uma serra a chapa de madeira; redesenhando a linha reta exata produzida pela faca que cortou o material adquirido na marcenaria. A exatidão interessa profundamente a esse artista, e ele gosta de exercitar a sua sobre a que já vem dada pelos materiais que recebe, seja ele uma folha de papel ou uma chapa de madeira. Tanto desenha com o lápis quanto com a serra, como também é capaz de pintar com lápis de cor, tinta acrílica, crayon, esmalte, goma laca, encáustica, sobre tecido, tela, chapa e compensado de madeira, por aí vai.

Baravelli desenha e pinta a partir de tudo, incorporando tudo a sua volta, e o faz com uma desenvoltura nessas duas linguagens que faz lembrar a facilidade com que Da Vinci escrevia com as duas mãos, e com uma capacidade de trabalho que faz as gerações mais novas, pouco afeitas a meter a mão na massa, se encolherem de medo.

Mas estou me adiantando. Faz tanto tempo que Luiz Paulo Baravelli não expõe no Rio, e precisou de uma galeria paulista resolver fixar-se aqui para que isso acontecesse, que me parece que seja o caso de se fazer uma breve apresentação dele. Afinal, o público carioca, especialmente o mais jovem, não tem obrigação de saber quem é esse exuberante e influente talento, egresso de uma faculdade de arquitetura, um dos quatro únicos discípulos de Wesley Duke Lee, os outros eram José Resende, Carlos Fajardo e Frederico Nasser; militante do Grupo Rex (com os acima mencionados, mais Nelson Leirner e Geraldo de Barros); fundador da Escola Brasil, que marcou época na São Paulo silenciosa dos anos 1970, onde imperava o delegado Fleury, a face mais sinistra da ditadura militar.

A Escola Brasil era um oásis de pensamento e prática artística, uma mini-Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Laje, onde toda a biblioteca dos fundadores – Baravelli, Resende, Nasser e Fajardo – estava a disposição dos alunos, onde se trabalhava em todos os horários, pois a escola ficava permanentemente aberta. Baravelli era professor e que professor! E, não bastasse isso, integrou o núcleo fundador da Revista Malasartes, ousada publicação carioca subsidiada por paulistas, outra aragem naqueles anos e, já nos anos 1980, fundou a linda revista Arte em São Paulo, trazendo Lisette Lagnado e Márion Strecker para trabalharem como editoras.

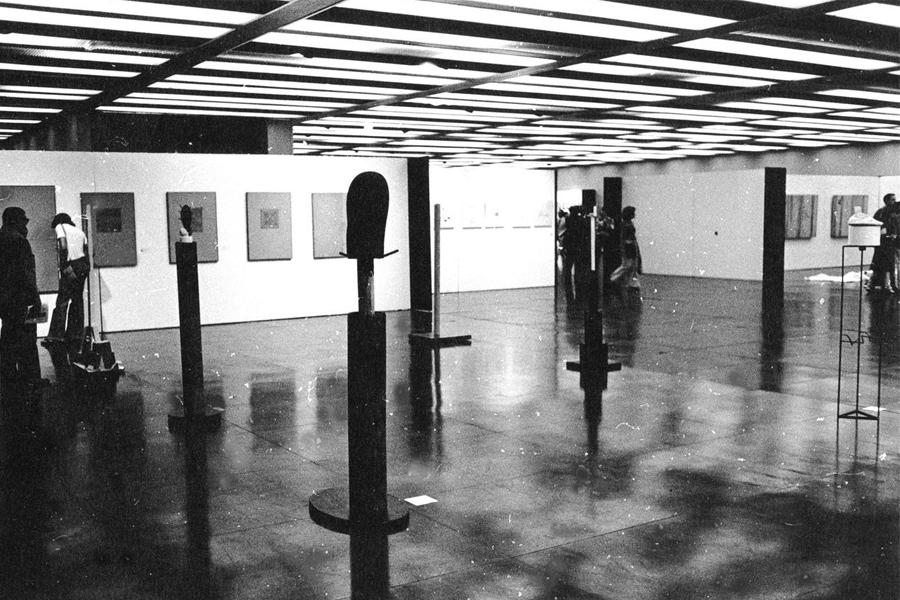

Voltando ao comentário de sua prática combinada de desenho e pintura, sem diminuir seu domínio pela tridimensional, aqui representada por quatro obras da série Acessórios para paisagem do Krazy Kat, apresentada em meados dos 1970 aqui mesmo, no MAM-RJ, cabe lembrar algumas de suas distinções entre desenho e pintura, entre desenhar e pintar: “desenhar é ver de perto”, enquanto pintar “é ver de longe. A pintura é premeditada, retórica, cultural”. A coisa vai mais longe. Parafraseando Valery, que desenhava para ver melhor, Baravelli desenha para perceber e prossegue defendendo que pinta para explicar, pois “o desenho é um instante da intimidade, ao contrário, a pintura é pública”. O artista cultiva a intimidade como uma flor delicada. Há décadas vive numa casa distante da metrópole, longe do barulho e da agitação, que evita na medida do possível, e trabalha noite adentro, quando a escuridão e o silêncio ilha seu atelier. Lá dentro ele vai operando nas várias frentes que compõem seu trabalho, o que vai do desenho de observação de um modelo vivo – “A noite, no silêncio e isolamento do estúdio, duas pessoas, um metro uma da outra, generosamente se deixando olhar”- a todas as etapas técnicas de seu trabalho, o que compreende cortar, pregar, colar etc, mais a filtragem, a edição de suas diversas fontes, sobretudo as visuais.

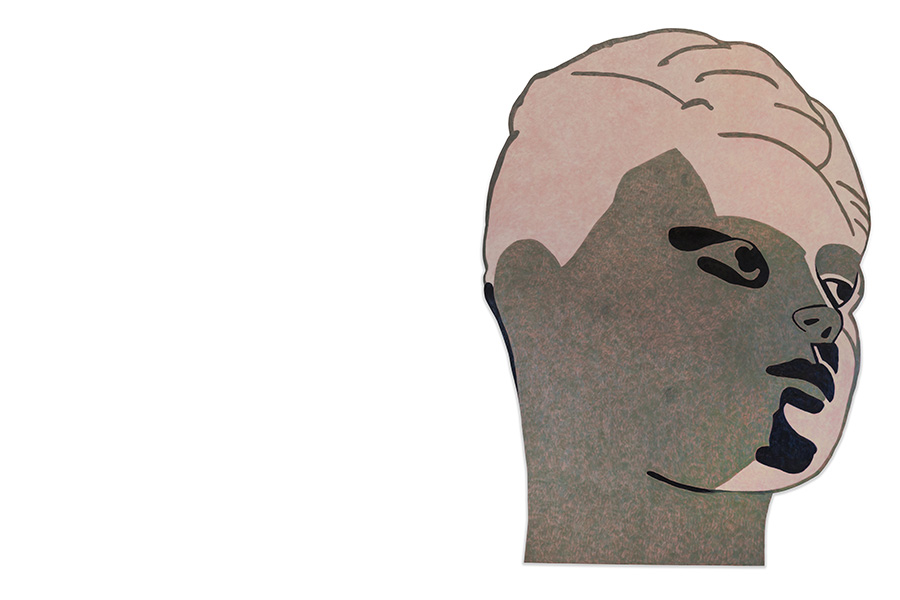

Foi mesmo acertada a decisão de se trazer para o Rio de Janeiro uma parte da série de Cabeças, um conjunto que retoma a produção com a qual ele representou o Brasil na Bienal de Veneza, em 1984. Cada uma delas com as dimensões de 220 x 160 cm, aproximadamente, gigantismo que lhes amplia o mistério. Rostos, retratos, pertencem a um dos gêneros mais férteis da história da arte, posto que com ele ampliou-se a dimensão enigmática do outro, a tentativa de uma representação que desvelasse, no nível da superfície da pele, o que vai por dentro do retratado. Dois aspectos cabem ser sublinhados nesse conjunto de cabeças: em primeiro lugar, o controle na conjugação entre desenho e pintura. Em Viena, por exemplo, o desenho das linhas de contorno do rosto parecem incendiar-se com a pintura, enquanto na Recém-casada, o desenho em preto desses mesmos traços do rosto feminino, mais os cabelos, as covas dos olho e o plano da boca, engrossa-se, chapa-se e disputa espaço com o vermelho. O Rapaz-Azul brinca com a herança picasseana, jogando com dois tempos de uma mesma face, lateralmente mais clara, frontalmente mais escura, mais intimista, e com os dois olhos replicados, saltando, compondo com a borda sinuosa da sombra, com o ondulado dramático do cabelo despenteado. Já Mysterious Bahia apresenta-se como vista frontal de um rosto que não sabemos se é uma pedra ou a superfície turva de um material recortado como uma cabeça. Sobre ele, sobre suas rugas e inscrições circulares e orgânicas, semelhantes a olhos, nariz e boca, um segundo desenho, este tosco de contornos pretos, o desenho garatujado de uma segunda cara.

O segundo aspecto a ser sublinhado, remete justamente ao modo como Baravelli joga com referências totalmente díspares, a ponto de alguém desavisado supor que se trata de uma exposição coletiva cujo tema era “cabeça’, e que todos deviam lidar com o mesmo suporte e com as mesmas dimensões. Notável sua erudição, assim como é notável seu interesse por tudo. Lembro-me perfeitamente de uma magnífica mostra antológica sua, realizada no Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP, no começo dos anos 1990, quando ele montou uma grande sala de formato elíptico para nela arranjar sua seleção de obras. No centro, sobre várias mesas, apresentou as inúmeras fontes de que se servia, de reproduções de obras clássicas de artistas a desenhos de arquitetos, imagens recolhidas em jornais, páginas de comics, propagandas etc. Era olhar na mesa para, em seguida, reconhecer nas pinturas, desenhos e esculturas, depois de muito olhar e pensar, fragmentos transpostos, metabolizados, grandemente modificados.

Poucos artistas são tão vorazes, poucos se servem, apropriam-se com tanto respeito e, por vezes, com nítida alegria, pelo que foi feito pelos outros. Em um breve e delicado artigo sobre uma sua exposição, Leonor Amarante colheu a deliciosa informação de que 338 artistas o influenciaram e continuam influenciando-o, não só pertencentes ao universo das artes plásticas como também do cinema e da literatura. Como também da história em quadrinhos, acrescentaria, sobretudo com a presença, junto dessas cabeças que ora são expostas, de exemplares da série dedicada ao incrível Krazy Kat, a obra prima de George Herriman, cuja conturbada relação entre o rato Ignatz e o gato (seria gata?), dava-se numa insólita paisagem onde tanto a arquitetura quanto a natureza eram respectivamente truncadas e absurdas. Absorvidas e elaboradas sob o peso do legado construtivo do artista, também essa produção revela-se como um mais tributo que ele faz à inteligência, não importa de onde ela venha.

Luiz Paulo Baravelli

by Agnaldo Farias

It comes from Matisse an essential instruction about the nature of a drawing: the first line in a sheet of paper is in fact the fifth. Few people realize that the edges of a work of art are part of it. That the work starts when the artist lean across the material – similar to what happens to football players, who, even before the game starts, by the time they sing the hymn, are not just singing, they are already playing. Always true to the principle of challenging boundaries, Luiz Paulo Baravelli begins each piece of this series of heads by drawing the wood plate with a saw; redrawing the straight line produced by the knife that has cut the material acquired at the woodshop. Accuracy deeply interests this artist, and he likes to practice his on the one that already exists in the materials he receives, either a sheet of paper or a wood plate. He draws both using pencil and saw, as well is capable of painting with color pencil, acrylic paint, crayon, enamel, shellac, encaustic technique, on fabric, canvas, plate, plywood and so on.

Baravelli draws and paints based on everything, incorporating everything around him, and he does it with such a fluency in both languages that resembles the easy way Da Vinci used to write with both hands, also with a working ability that makes the younger generations, less accustomed to get their hands dirty, cringe.

But I am getting ahead of myself. It has been a long time since Luiz Paulo Baravelli last exhibited in Rio, and it was necessary that a gallery from São Paulo decided to establish here in order to make it happen. So, I feel compelled to introduce him briefly. After all, the audience from Rio de Janeiro, especially the youngest, has no obligation of knowing who is this vivid and influent talent, alumni from a College of Architecture, one of the four disciples of Wesley Duke Lee – the others were José Resende, Carlos Fajardo and Frederico Nasser –, an activist for Rex Group (together with the ones previously mentioned, plus Nelson Leirner and Geraldo de Barros), founder of Brasil School, a place that defined an era in the silent São Paulo in the 1970s, where the rules were made by Inspector Fleury, the most eerie face of military dictatorship.

Brasil School was an oasis of artistic thinking and practice, a mini School of Visual Arts at Lage Park, where the entire founders’ library – Baravelli, Resende, Nasser and Fajardo’s – was available to the students, where it was possible to work all day long, because the school was permanently open. Baravelli was a teacher, and what a teacher! And, since that was not enough, he integrated the founding core of Malasartes Magazine, a bold carioca publication sponsored by paulistas, other breeze in those years and, in the 80s, he has founded the beautiful Art in São Paulo magazine, bringing Lisette Lagnado and Márion Strecker to work as editors.

Back to the comment on his combined practice of drawing and painting – without reducing his domain on the tridimensional, here represented by four works of the series Acessories to Krazy Kat’s landscape, presented in mid-1970s in this same place, MAM-RJ –, it is worth remembering some of the differences he sees between drawing and painting: “to draw is to see closely”, while to paint “is to see from afar. The painting is foreseen, rethoric, cultural”. The issue goes further. Paraphrasing Valery, who used to draw to see better, Baravelli draws in order to comprehend and he keeps defending that he paints to explain, because “the drawing is an instant of intimacy, in opposition, the painting is public”. The artist cultivates the intimacy as a delicate flower. Since decades, he lives in a house far from the big city, far from the noise and agitation, which he avoids as much as possible, and works all night long, when the darkness and the silence isolate his atelier. Indoors, he operates in the several divisions that compose his work, which go from the observational drawing of a live model – “At night, in the silence and isolation in the studio, two people, separated by the distance of one meter, kindly let themselves look at each other” – to all the technical stages of his work, which consist in cutting, nailing, pasting etc, plus the filtering, the editing of his diverse sources, especially the visual ones.

Bringing to Rio de Janeiro one part of the series of “Heads” was a right decision. This set resumes the production with which he represented Brazil at the Venice Biennale in 1984. Each of them has the approximate dimensions of 220 x 160 cm, a hugeness that broaden their mystery. Faces, portraits, belong to one of the most fertile genres in the history of Art, given that it has expanded the enigmatic dimension of the other, an attempt of a representation that would reveal, at the skin-surface level, what goes inside of the portrayed person. Two aspects must be highlighted in this set of heads: in first place, the control of the combination of drawing and painting. In “Vienna”, for instance, the drawing of two contour lines of the face seems to catch fire within the painting, while in “Just-Married”, the drawing in black of these same traits of the feminine face, plus the hair, the eye holes and the mouth plan, thickens, falls flat and fights for space with the red. “The Blue-Guy” plays with the Picassean inheritance, working with two moments of a same face, lighter in the sides, darker in the front, more intimate, and with the two eyes replicated, jumping, composing with the sinuous edge of the shadow, with the dramatic waving of the unkempt hair. “Mysterious Bahia” is presented as a front view of a face that we do not know whether it is a stone or a turbid surface of a material cut in the shape of a head. Over it, over its circular and organic wrinkles and inscriptions, similar to eyes, nose and mouth, a second drawing, this lug of black outlines, the scratched drawing of a second face.

The second aspect that needs to be highlighted refers precisely to how Baravelli plays with completely different references, in such a way of a distracted person may assume that it is a collective exhibition whose theme was “head”, and that everybody was supposed to deal with the same support and with the same dimensions. His erudition is remarkable as well as his interest for everything. I perfectly remember of a magnificent anthologic exhibition he made at USP’s Museum of Contemporary Art, by the beginning of 1990s, when he built a big room shaped as an ellipsis in order to organize inside it his selection of works of art. In the center, over several tables, he presented the uncountable sources he used: from reproduction of classic works of artists to architects’ drawings, images taken from newspapers, comic books pages, advertisements etc. We had to look at table and then recognize in the paintings, drawings and sculptures – after a long time looking and thinking – fragments transposed, metabolized, largely modified.

Few artists are so voracious, few of them use, appropriate, with so much respect and sometimes pure joy, what has been done by others. In a brief and delicate article about one of his exhibitions, Leonor Amarante collected the information of 338 artists who has influenced him and keeps influencing, not only those who belongs to the universe of plastic arts, but also of the cinema and literature as well. Not to mention the artists from comic books, especially due to the presence, together with the heads exposed at the moment, of pieces from the series dedicated to the incredible Krazy Kat, the masterpiece of George Herriman. The story about a troubled relationship between the mouse Ignatz and the cat (would it be a cat?) took place in a strange landscape where architecture and nature were respectively truncated and absurd. Absorbed and created under the weight of the constructive legacy of the artist, this production also proves to be more a tribute that he pays for intelligence, no matter where it comes from.