galeria marcelo guarnieri | rio de janeiro

abertura/opening

19.11.2016 / 14h – 17h

November 19, 2016 / 2 – 5pm

período de visitação/exhibition

19.11.2016 – 21.01.2017

Rua Teixeira de Melo, 31 – lojas C/D

Ipanema – Rio de Janeiro – Brasil

[ mapa/map ]

LIUBA NO RIO DE JANEIRO

por Maria Alice Milliet

1965. Nesse ano foi inaugurado o parque do Flamengo no contexto das comemorações do IV Centenário do Rio de Janeiro. Construído sobre aterros sucessivos na baía de Guanabara, abrigando pistas de alta velocidade, passarelas elegantes e equipamentos desportivos e culturais abertos à população, o parque, com a implantação do projeto paisagístico de Burle Marx, se tornou referência internacional pela beleza e exuberância de sua vegetação. Seu traçado urbanístico foi concebido pelo arquiteto Affonso Eduardo Reidy, também responsável pelo desenho de alguns dos monumentos situados ao longo da orla marítima. Dentre eles, um se tornou emblemático da arquitetura racionalista de meados do século XX: o Museu de Arte Moderna. Localizado numa das extremidades do aterro, o edifício em concreto armado funciona como pórtico de acesso à imensa área ajardinada.

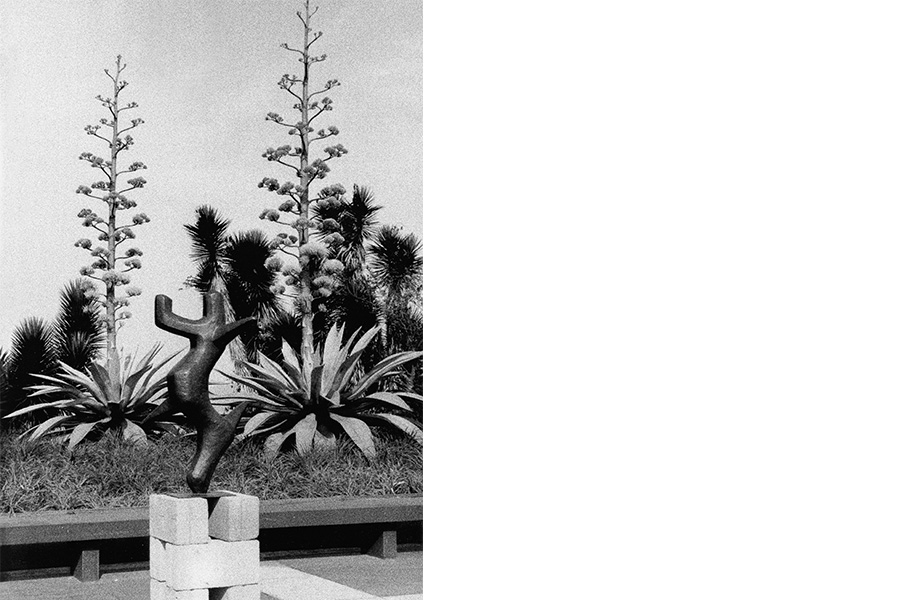

Foi nesse cenário grandioso que as esculturas de Liuba vieram se instalar quando de sua exposição individual no MAM-RJ, há cinquenta anos. As obras, dispostas em bases e muros baixos formados por blocos de cimento, foram locadas no pavimento térreo, sob a cobertura e ao longo da lateral externa do prédio de modo a dialogar tanto com a arquitetura do museu como com a área verde ao seu redor. O registro fotográfico da mostra, publicado no livro Liuba: At the Edge of Abstraction¹, revela a intensidade das relações formais estabelecidas entre o conjunto escultórico e o entorno, seja natural, seja construído. A sinergia entre os modos de expressão – arquitetura, paisagismo e escultura – advém da afinidade de propósitos dos autores envolvidos, todos empenhados em participar ativamente do espaço urbano no âmbito da modernidade.

“Tenho estado particularmente interessada na ligação entre escultura e arquitetura”², declarou Liuba, no mesmo ano da mostra no Rio de Janeiro. Como se pode ver nas fotografias de época, a concisão formal de sua obra escultórica encontra eco no rigor construtivo da arquitetura de Reidy. Mais que isso, é notável a correspondência entre as formas angulosas, até mesmo agressivas, dos bronzes, e a estrutura do museu, composta por 14 pilares em V alinhados como se fossem as vértebras de um esqueleto gigantesco: na arquitetura assim como na escultura, a tensão gerada pela dinâmica das formas permanece sob controle.

O biomorfismo severo, quase abstrato do repertório escultórico de Liuba provém da transfiguração dos mundos animal e vegetal. “Minha expressão pessoal se inspira em toda sorte de formas naturais.”³ A relação com a natureza se torna mais evidente quando as esculturas são instaladas ao ar livre. Foi o que aconteceu na área ajardinada junto ao MAM, cujos canteiros preenchidos por seixos gigantes e plantas exóticas, como queria Burle Marx, tão bem acolheram aquelas criaturas em bronze. Nenhum estranhamento. Ao contrário, as esculturas parecem ter encontrado seu hábitat.

A ampla interação que acabamos de descrever ilustra o momento de maturidade bem-sucedida a que chegou o modernismo brasileiro em meados do século XX. A obra de Liuba teve no Rio a oportunidade de integrar, ainda que momentaneamente, um dos mais ousados projetos urbanísticos do pós-guerra. Ali, a artista pôde dar sua contribuição, ali se sentiu em casa.

Para Liuba, esse sentimento de pertencimento foi sempre uma questão em aberto. Nascida em Leipzig, na Alemanha, em 1923, durante uma viagem de seus pais, viveu sua infância em Sofia, na Bulgária e se tornou cidadã brasileira três décadas depois. Na juventude, vivendo num meio culto e burguês, pôde se dedicar a estudos de literatura e música. Porém, no começo da Segunda Guerra, a ocupação do seu país pelos soviéticos determinou a mudança da família para Genebra. Na Suíça, Liuba encontrou sua vocação. Conheceu Germaine Richier, renomada escultora da Escola de Paris, com quem trabalhou de 1943 a 1949 nos estúdios de Zurique e Paris. Com ela aprendeu tudo sobre a técnica tradicional de escultura em bronze: modelagem do original em argila, contramolde em gesso, fundição em cera perdida, pátinas. A década de 1950 foi para Liuba um período de afirmação. Estabeleceu seu próprio ateliê em Paris e fez inúmeras viagens pela Europa, Estados Unidos, norte da África e América do Sul. Finalmente, montou um estúdio em São Paulo, onde seus pais já residiam. Seu processo de emancipação chegara ao fim. Desde 1957 estava em busca de uma linguagem própria. Nesse ano, realizou um Nu de grande porte, prenúncio de uma linguagem pessoal, inconfundível. Em 1958, conheceu o empresário Ernesto Wolf, com quem se casou.

O casal passaria a residir parte do ano em Paris, o que lhes permitiu um permanente contato com a arte internacional. Ao mesmo tempo, o interesse por civilizações desaparecidas e pela arte tribal levou-os a visitar locais onde os vestígios de culturas ancestrais ainda podiam ser apreciados. Acabaram por reunir requintada coleção de arte africana. A década de 1960 foi de grande atividade para ela. A artista participou de importantes coletivas, tais como a Bienal de São Paulo (1963, 1965 e 1967), o Salão Nacional de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (1962-1963) e o Salon de la Jeune Sculpture de Paris (1964-1979). Assim, a mostra individual no MAM-RJ ocorreu na esteira de um crescente reconhecimento da artista.

Sua plástica, ancorada na tradição da escultura moderna na linha de Brancusi e Giacometti, se alimenta, simultaneamente, da simplificação formal introduzida pelo cubismo e da arte de culturas exóticas. Como se sabe, essas duas vertentes estiveram associadas às vanguardas artísticas que no início do século romperam com as convenções da academia. A produção escultórica de Liuba bebeu nessas fontes, chegando à maturidade durante o alto modernismo, período em que a estética moderna ganhou alcance internacional.

Apesar de usufruir da aceitação que a linguagem moderna havia alcançado, a obra de Liuba não deixa de ser inquietante. Em muitas de suas criações – um bestiário de seres híbridos, alguns semelhantes a pássaros –, os membros retesados, as torções vigorosas e a boca escancarada dos animais são indícios de violência. Expressões de terror e agressividade semelhantes aparecem na cabeça de cavalo, figura central da tragédia de Guernica (1937) pintada por Pablo Picasso, ou nas Irínias (fúrias vingativas), três estudos que Francis Bacon pintou para a base do painel da Crucificação (1945). O sentido trágico dessas representações nos remete à angústia do mundo contemporâneo. Liuba reage a esse sentimento com energia. Suas figuras monumentais estão prontas para lutar pela existência.

_________

¹ HUNTER, Sam. Liuba: at the edge of abstraction. Nova York: Rizzoli, 2001.

² Entrevista com Liuba. Chefs d’oeuvre de l’art, n. 105, 1965.

³ Idem.

LIUBA IN RIO DE JANEIRO

by Maria Alice Milliet

1965. In this year, Flamengo Park was inaugurated during the celebrations of Rio de Janeiro’s 4th centennial. Built over successive landfills on Guanabara Bay, housing fast lanes, fancy footbridges, and sports and cultural equipment open to the public use. The park, with the implementation of Burle Marx’s landscape project, has become an international reference due to the beauty and exuberance of its vegetation. Its urbanistic tracing was conceived by the architect Affonso Eduardo Reidy, also responsible for designing some of the monuments located throughout the waterfront. Among them, one has become a symbol of the rationalist architecture from the mid-twentieth century: the Museum of Modern Art (MAM). Located in one of the end-points of the landfill, the building made of reinforced concrete serves as an access porch to the immense garden area.

It was in this magnificent scenery that the Liuba’s sculptures settled during her individual exhibition at MAM-RJ fifty years ago. The works of art, placed in bases and low walls made by cement blocks, were located at the ground floor, under the roofing and throughout the external sideline of the building in order to dialogue not only with the museum architecture, but also with the surrounding green area. The photographic register of the show, published in the book At the Edge of Abstraction¹, reveals the intensity of the formal relations established between the sculptural set and its vicinity, either natural or constructed. The synergy between the different means of expression – architecture, landscaping and sculpture – comes from the affinity between the artists involved, all of them engaged in actively participating on the urban space in the age of modernity.

“I have been particularly interested in the link between sculpture and architecture”², declared Liuba, in the same year of her solo exhibition in Rio de Janeiro. As we can see at the pictures, the formal concision of her sculptural work finds an echo in the constructive strictness of Reidy’s architecture. Moreover, it is remarkable the correspondence between the angled, even aggressive, forms of the bronzes, and the structure of the museum, composed of 14 pillars aligned in V as if they were the vertebrae of a gigantic skeleton: in the architecture as well as in the sculpture, the tension generated by the dynamics of the forms stays under control.

The severe biomorfism, almost abtract, from Liuba’s sculptural repertory comes from the transfiguration of the animal and vegetal worlds: “… my personal expression is inspired by all kinds of natural forms.”³ The relation with the nature becomes more evident when her sculptures are set up outdoors. That happened in the garden area next to MAM whose flower beds filled with gigantic pebbles and exotic plants, following Burle Marx’s wishes, has welcomed very well those bronze creatures. No strangeness. On the contrary, the sculptures seem to have found their habitat.

The large interaction we have just described illustrates the well-succeeded mature moment that Brazilian Modernism has reached in the mid-twentieth. in Rio, Liuba’s work had the opportunity to integrate, even though for a moment, one of the boldest post-war urbanistic projects. There, the artist could give her contribution, there she felt like home.

For Liuba, that feeling of belonging has always been an unresolved issue. Born in Leipzig, Germany, in 1923, during a journey done by her parents, she lived her childhood in Sofia, Bulgaria, and has become a Brazilian citizen three decades later. In her youth, living in an educated and bourgeois environment, she could dedicate herself to the studies of Literature and Music. However, in the beginning of the Second World War, the occupation of her country by the soviets determined the family moving to Geneva. In Switzerland, Liuba found her inclination. She met Germaine Richier, renowned sculptor of Paris School, with whom she worked from 1943 to 1949 at the studios in Zürich and Paris. She learned with her everything about the traditional technique of bronze sculpture: modelling from the original in clay, counter mold in plaster, lost-wax casting, patinas. The decade of 1950s was an assertion period for Liuba. She established her own atelier in Paris and travelled many times to Europe, United States, North of Africa and South America. She was seeking for a personal expression. In 1954, she began to explore freeform sculpture of animal and vegetal inspiration. Eventually, she set up a studio in São Paulo, where her parents were already living. In 1958, her emancipation process had come to an ending. This year, she met the entrepreneur Ernesto Wolf, to whom she married.

The couple would live part of the year in Paris, which has allowed them a permanent contact with international art. At the same time, the interest in missing civilizations and tribal art led them to visit places where the remains of ancestral cultures could still be relished. Along the years, they gathered a sophisticated collection of African art. The decade of 1960 was of intense activity for her. The artist participated in important group exhibitions, such as São Paulo Biennial (1963, 1965 and 1967), Salão Nacional de Arte Moderna in Rio de Janeiro (1962-1963) and the Salon de la Jeune Sculpture de Paris (1964-1979). Thus, the individual exhibit at MAM-RJ took place in the trail of a growing recognition of the artist.

Her plastic language, anchored in the tradition of modern sculpture on the line of Brancusi and Giacometti, nourishes itself of the formal simplification introduced by Cubism inspired by the art of exotic cultures. As we know, this approach was associated to the artistic avant-gardes, which broke with the academic conventions in the beginning of the last century. Liuba’s sculptural production draws on these sources, reaching maturity during high modernism, when the modern aesthetics obtained international acclaim.

Although joining the acceptance that modern language has reached, Liuba’s work never cease to be disquieting. In many of her creations – a bestiary of crossbreeds, some similar to birds –, the animals’ stiff limbs, the vigorous twisting and the wide-open mouth are all evidence of violence. Similar expressions of terror and anger appear on the horse head, central image of the tragedy of Guernica (1937) painted by Pablo Picasso, or on the Eumenides (vengeful furies), three studies that Francis Bacon painted for the base of the Crucifixion panel (1945). The pathos of these representations do reveal an almost unbearable anguish. Liuba reacted to this feeling with energy. Her monumental figures are ready to fight for existence.

_________

¹ HUNTER, Sam. Liuba: at the edge of abstraction. Nova York: Rizzoli, 2001.

² Interview with Liuba. Chefs d’oeuvre de l’art, n. 105, 1965.

³ Idem.