galeria marcelo guarnieri | rio de janeiro

abertura/opening

18.06.2016 / 11h – 17h

June 18, 2016 / 11am – 5pm

período de visitação/exhibition

18.06 – 23.07.2016

Rua Teixeira de Melo, 31 – lojas C/D

Ipanema – Rio de Janeiro – Brasil

[ mapa/map ]

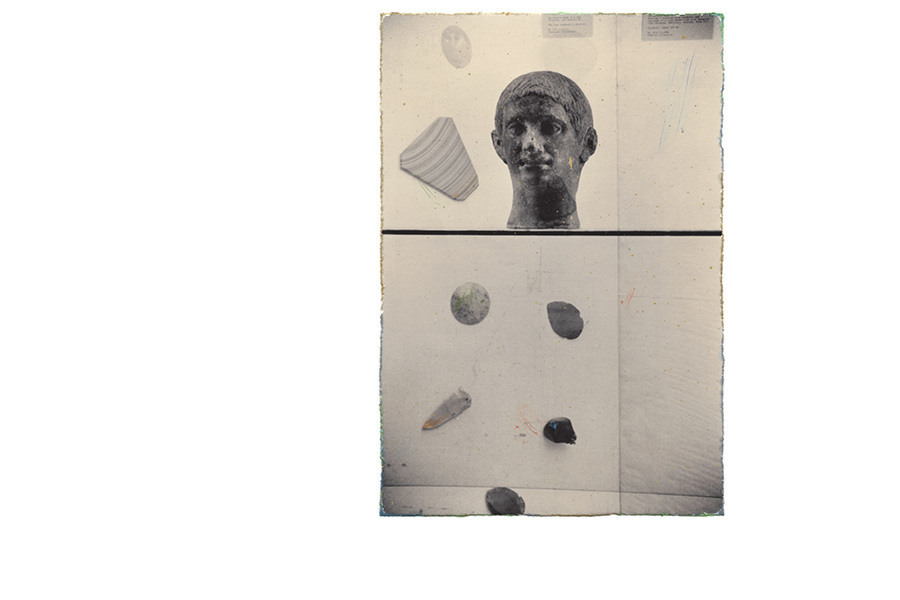

Dimensões

As fotografias de Masao Yamamoto têm pequenas dimensões, a maioria delas, como declara o artista, cabe na palma da mão, como um pequeno objeto que recolhemos e olhamos com cuidado, como um pássaro que agarramos com surpresa e ternura, desejando acalmar o ritmo frenético do seu coração, aplacar seu medo e ânsia de fugir da prisão momentânea dos nossos dedos cingidos sobre seu corpo, como se lhe fosse possível entender a curiosidade e o amor que nos impele reter sua beleza delicada. Yamamoto acerta no alvo realizando fotos de escala reduzida, algumas delas frágeis, com as bordas rasgadas, a maior parte passível de ser apanhada pelas pontas dos dedos ou depositada na mão, relembrando-nos que dedos e palmas são a mesa de contemplação das coisas pequenas, dos objetos trazidos para perto dos olhos, para serem bem vistos, apalpados e cheirados. Haverá possibilidade maior de contato entre nós e tudo aquilo que a mão traz para o nível do olhar? É difícil, ao menos do ponto de vista onde o afeto funde-se à vontade de conhecer. Contemplamos o mundo à distância, desde o alto de nossas cabeças, encastelados num corpo que, em geral, não cessa de se movimentar. Quase nunca paramos e mesmo quando paramos nunca estamos. Há em cada um de nós uma nostalgia da permanência, do simples exercício de ficar e olhar em volta. Olhar calmamente atento ao que está acontecendo ao redor do nosso corpo.

A escala das fotos de Masao Yamamoto, por si só, convida a esse modo de estar no mundo. Gatos, cachorros, pássaros, árvores, galhos, pedras, montanhas, praias, água, neve, grama, vasos, flores, pessoas, nus, a maioria dos assuntos parece resultar de seus passeios munido de câmera e de atenção.

E a atenção, ensina o artista, nunca é passiva. Em um determinado momento do vídeo intitulado “O espaço entre flores”, vemo-lo fotografando um grupo de pombas. Câmara na mão direita, comida sendo jogada aos punhados aos pássaros pela outra, abruptamente um grupo de crianças espanta-as com seu alarido. Elas voam desorganizadas enquanto ele as vai fotografando como um caçador abatendo a esmo um bando em revoada. Em seguida, de volta ao chão, os pássaros vão comendo os grãos, enquanto alguns, mais ousados, bicam dentro da concha da mão. A mão da câmara acelera seu trabalho, coordenando-o com o da direita. Esta, com um único pássaro nela empoleirado, vai se elevando, prossegue com o artista se erguendo, até colocar o pombo no alto, contra o fundo claro do céu. Na sequência, o vídeo dá-nos algumas imagens obtidas da confusão branca e cinza de asas e corpos.

Como é comum em suas fotos, o objeto da atenção do fotógrafo reage aos seus gestos, as suas ações no espaço. Neste caso em particular, como em alguns outros casos, o objeto da atenção do fotógrafo está ao alcance e pousado em sua mão. Como as dimensões da foto que ele realizará a partir de situações como essa.

O que se olha revela cada uma das imagens produzidas por Masao Yamamoto e que ele expõe diretamente sobre a parede, como um enxame esgarçado de imagens, ou flutuando no centro de um grande quadrilátero de papel, depende de como se olha, tanto quanto depende da luz que, banhando-o, inventa-o.

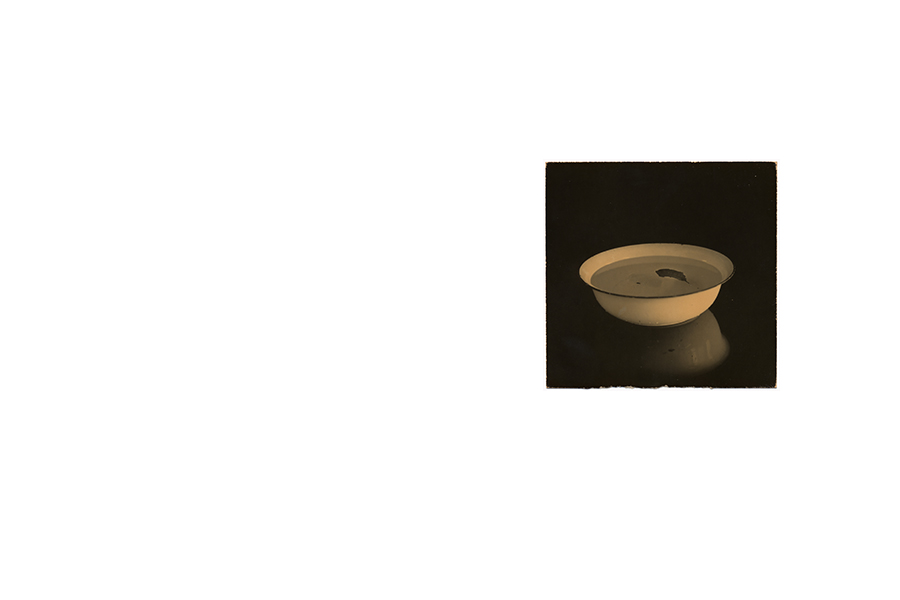

Luz

“A captura da luz é a essência da fotografia. Estou mais do que nunca convencido de que a fotografia foi criada quando os humanos desejaram capturar a luz”. Essa declaração de Masao Yamamoto explica a predominância do preto e branco em suas fotografias, conquanto um exame atencioso delas, um impulso natural decorrente de suas pequenas dimensões, algumas delas efetivamente minúsculas, revelará que a polaridade entre essas duas cores é, na verdade, calibrada pela adição calculada de cores esmaecidas, como os planos claros realizados em tonalidades rebaixadas de creme e amarelo, turvados aqui e ali por pontos escuros, como papéis envelhecidos ou fotos descoradas pela ação do tempo em associação com a luz; como os planos tingidos de preto profundo, aveludado, insaciável ao sorver a luz mais próxima.

O trabalho iniciado nas caminhadas pela natureza observando as minúcias de cenas e objetos que passam despercebidos, ou os acurados estudos efetuados dentro do estúdio, expressos em naturezas mortas e sucessões de ângulos de um mesmo objeto, prolongam-se nos processos de impressão e ampliação, no controle paciente e obsessivo da luz que se irradia do alto da lâmpada da ampliadora até o chão do papel fotossensível. A fotografia, segundo Masao Yamamoto, não se resolve no simples registro do visível, mas na produção de uma imagem que, como tal, nasce do equilíbrio tenso entre o fotógrafo e o fragmento do mundo; um fragmento do visível que ele torna seu, que, por apropriação, só pode ser seu, um visível a sua maneira. E é sob esse prisma, pela consciência de que cabe a ele, através da luz, fazer com que as parcelas selecionadas do mundo floresçam como imagens, que ele a realça como instância fecundadora, capaz de resgatar as coisas do eclipsamento ao qual nossa desatenção condena.

Em suas imagens as regiões iluminadas opõem-se as tomadas pelas trevas, como acontece naquela dividida em dois planos empilhados, uma paisagem em que sobre o chão silencioso e obscuro, estende-se o céu claro ainda que suavemente ensombrecido. Entre ambos, funcionando simultaneamente como limite e invasão de um plano no outro, os pilares claros de uma trave de futebol fendem verticalmente o solo enquanto a terceira linha roliça parece retificar a do horizonte. Em outra imagem a luz vem do alto dos dois renques espessos de vegetação para escorrer pela fenda aberta entre elas, fazendo brilhar o caminho por onde transitam duas pequenas silhuetas humanas. O mesmo raciocínio vale para o portal irregular, inclinado, esculpido na pedra, por onde jorra a luz que desenha na tona d’água, em solução difusa, o desenho de suas bordas rígidas. E o quê dizer da lua, minguante? Crescente? Tornada imensa por ser o centro iridescente que se apoia sob o vértice sombrio da cobertura da casa, imantando a noite com seu halo?

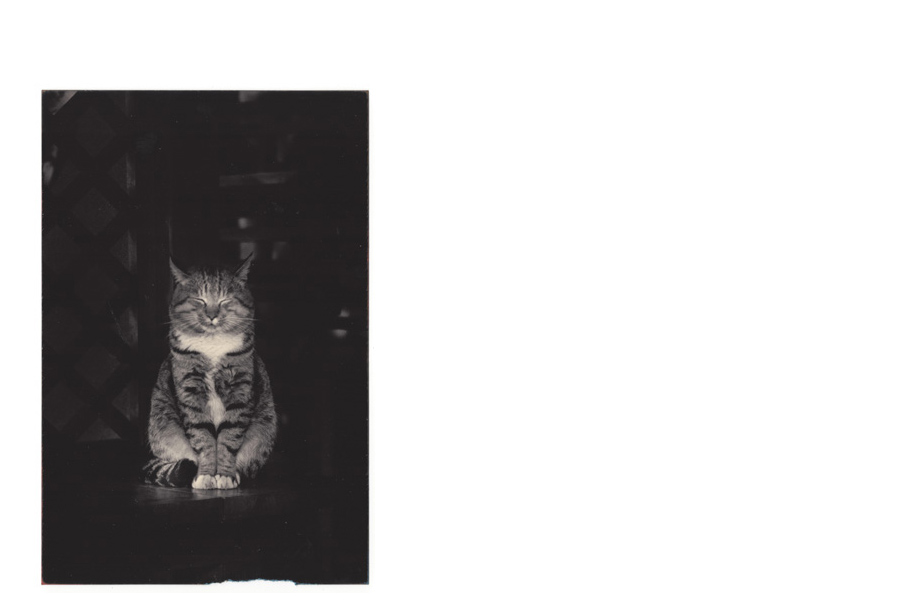

Masao Yamamoto parece dizer que cada homem define um círculo iluminado, uma região que lhe serve de abrigo em oposição aquilo que ele desconhece e que o desafia. Conhecer é, por sua vez, lançar luz sobre a escuridão, como a luz que redesenha o peito do gato, o olhar vítreo do cachorro, tornando enigmático, profundo e transcendente, o que se supunha familiar e doméstico. A dialética proposta por Yamamoto entre a luz e as coisas, por mais simples, familiares que estas sejam, vai ao encontro do belo aforismo de Georges Braque: “O mistério brilha à luz do dia; o misterioso se confunde com a obscuridade.

Pontos de vista

A imagem, já referida anteriormente, é de uma paisagem dotada de um horizonte retilíneo, dividindo o campo retangular da foto em dois planos empilhados, um escuro, o chão, o outro, um pouco maior e claro, o céu. Uma paisagem simples, despojada, sem acidentes, salvo uma trave de futebol situada bem no meio, cujo travessão coincide rigorosamente com a linha do horizonte. Essa informação é suficiente para que a identifiquemos como a vista parcial de um campo de futebol que, não se sabe, acontece para a direita ou para a esquerda. Detalhe de resto irrelevante, posto que o que atrai nossa atenção é a deformação imposta à moldura do gol. Apesar do paralelismo do travessão com o solo, certeza que se confirma pela coincidência com a borda reta da paisagem, as traves verticais são muito dessemelhantes, a da esquerda bem maior que a da direita. Uma deformação que não haveria se o fotógrafo tivesse limitado os ângulos de visão aos possíveis de serem obtidos de pé sobre o chão, mas explicável se se imagina que ele subiu em algo, por exemplo, uma escada, com a finalidade de criar uma coincidência.

Situado quase no centro, levemente deslocado para a esquerda da fotografia de formato vertical, com o tom sépia típico das que eram acondicionadas em velhos álbuns, efeito acentuado pela lateral levemente rasgada e pelo resguardo de uma espécie de fina moldura formada pelos limites do papel, um gato preto sentado. Sua silhueta escura e aveludada está circundada por florações vagas e esparsas e pelo dorso de uma pedra. Do seu corpo curvilíneo como uma pêra, escapa, à direita, seu rabo preto. Entre as orelhas em riste, coroando sua impassível e silenciosa presença, luzem as lanternas amendoadas de seus olhinhos. Ele, o gato, está no chão, já o fotógrafo, aqui no alto. Aqui, isto é, onde nós que nesse momento contemplamos esta foto, estamos; o lugar que o fotógrafo nos obriga a estar. Visto de cima, pequeno, Yamamoto, graças ao ponto de vista escolhido, reitera: a majestade do gato reside em sua pose; e em seu porte, sua cor e suas luzes, todo o mistério.

O formato da foto é horizontal como uma paisagem, mas, no entanto, ela traz, capturado à queima roupa, ocupando todo sua extremidade esquerda, contrastando com a claridade creme do resto através de gradações em direção ao preto, parte do perfil de um rosto com os olhos fechados, a boca entreaberta. A esfericidade das pálpebras traem a proveniência oriental da pessoa retratada, esfericidade enunciada pela luminosidade que suavemente vai se alastrando na pele sedosa, sem rugas ou comissuras, cinzelando, além dos olhos, a maçã da face, o lóbulo da narina, repercutindo na ínfima parcela visível da fileira superior de dentes, a curva abaixo do lábio inferior, a passagem do queixo para o pescoço. O desenho sinuoso do perfil, debuxado pela luz, interrompe-se no formato retangular da foto que recorta a figura. Um rosto escuro face a um plano cuja cor pálida, pintalgada por pequeninos pontos, o acaricia. A boca entreaberta estará expirando? Aspirando? Como saber? O que é certo é que, sorvendo ou recebendo o impacto do claro, é a luminosidade que faz nascer um rosto do interior da sombra, que o puxa de dentro dela.

Corrigindo o escrito antes, Masao Yamamoto não se ocupa de situações objetos e seres familiares, apenas. Ocupa-se também da relação entre eles, da intrincada relação entre eles e a luz, entre eles e os formatos escolhidos para as fotos, entre eles e sua relação com seus pontos de vista inquietos, cambiantes, surpreendentes.

Agnaldo Farias / crítico e curador / Professor da FAUUSP

Dimensions

Masao Yamamoto’s photographs are small – most of them, as the artist states, fit in the palm of the hand, like a small object that we gather and look at with care, like a bird that we grasp with surprise and tenderness, seeking to calm its frantic heartbeat, placate its fear and eagerness to flee from the momentary prison of our fingers, encircling its body, as though it were possible for it to understand the curiosity and the love that urges us to hold its delicate beauty. Yamamoto hits the mark by producing small-scale photos, some of which are fragile, with torn edges, and most of which can be held by one’s fingertips or laid on one’s hand, reminding us that fingers and palms are the table for the contemplation of small things, of objects brought close to the eyes, to be better seen, touched and smelled. Could there be any greater contact than the one we have with something our hand brings to the level of our gaze? There hardly could, at least from the point of view where our feeling is blended with the desire to know. We contemplate the world from a distance, from the height of our heads, set atop a body that generally does not stop moving. We seldom stop, and even when we do, either we or our context are still somehow in movement. We each carry a nostalgia of permanence, of the simple exercise of standing still and looking around ourselves. Looking calmly, paying attention to what is happening around our body.

The scale of Masao Yamamoto’s photos, in and of itself, is an invitation to this way of being in the world. Cats, dogs, birds, trees, branches, stones, mountains, beaches, water, snow, grass, vases, flowers, people, nudes – the majority of the subjects seem to result from walks he takes with an attentive eye, camera in hand.

And such attention, the artist teaches, is never passive. At a determined moment in the video entitled “The Space Between Flowers“, we see him photographing a group of pigeons. He’s holding his camera in his left hand and tossing handfuls of food to the birds with the other, when a group of yelling children run by, scaring them away. They fly chaotically while he photographs them like a hunter taking potshots at an airborne flock. They return to the ground and continue eating the seeds on the ground, while some of the most daring ones walk up to peck at the kernels in his hand. The hand on the camera quickens the pace of its shooting, coordinating with the right hand. Then the right hand, with a pigeon perched on it, is raised higher and higher as the photographer continues photographing it, until it’s above eye level, against the bright background of the sky. As the video progresses it shows various images obtained in the white and gray confusion of bird wings and bodies.

As is common in his photos, the object of the photographer’s attention reacts to his gestures, to his actions in the space. In this particular case, as in some other ones, the photographer’s object of attention is within his reach and perched on his hand – just like the dimensions of the photo that he will print based on situations like this.

What one sees when observing each of the images produced by Masao Yamamoto, which he displays directly on the wall, like a torn beehive of images, or floating in the center of a large paper quadrilateral, depends not only on how one looks at it, but also on how the light bathes it, inventing it.

Light

“The capture of light is the essence of photography. I am more than ever convinced that photography was created when humans wanted to capture light.” This statement by Masao Yamamoto explains the predominance of black and white in his photographs, although a detailed examination of them – a natural impulse due to their small sizes, some of them downright miniscule – will reveal that the polarity between these two colors lies in the truth calibrated by the calculated addition of faded colors, such as the light-toned planes in discrete hues of green and yellow, speckled here and there with dark points, like aged paper or photos faded by the action of time in association with light; such as the planes dyed with deep, velvety black insatiably absorbing the closest light.

The work begun in his walks through nature, observing the details of scenes and objects that normally go unnoticed, or in the accurate studies he carries out in his studios, expressed in still lifes and shots taken of the same object from various angles, is extended in the processes of printing and enlargement, in his patient and excessive control of the light that shines down from the top of the enlarger onto the photosensitive paper. According to Masao Yamamoto, photography is not limited to the simple recording of the visible, but includes the production of an image which, as such, is born from the tense balance between the photographer and the fragment of the world; a fragment of the visible that he makes his own, which, by appropriation, can only be his, an object visible in his own way. And it is from this viewpoint, through the awareness that it is his task, by means of light, to make the selected portions of the world flourish like images, that he highlights it as a seminal instance, able to recover the things from the eclipsing our inattention condemns them to.

In his images, the lighted regions are opposed to the shadowy portions, as seen in the photo divided into two overlaid planes, a landscape in which a bright but overcast sky extends over a silent and dark ground. Between the two, functioning simultaneously as a border and in invasion of one of the planes into the other, the bright side posts of a football goal vertically fracture the soil while the third bold line of the crossbar seems to straighten the horizon. In another image the light shines down from above two thick rows of vegetation to effuse through the open slot between them, lighting up the path being tread by two small human silhouettes. The same reasoning applies to the irregular, slanting portal, carved in the rock, through which light filters and casts the design of the portal’s rigid borders on the diffuse tones of the water. And what can be said about the waning? waxing? moon made immense for being the iridescent center that rests on the gloomy vertex of a house roof, magnetizing the night with its halo?

Masao Yamamoto seems to say that each man defines an illuminated circle, a region that serves him as shelter as opposed to the unknown that lies outside, challenging him. To get to know something is to cast light on the darkness, like the light that redraws the cat’s breast, the glassy gaze of the dog, taking the supposedly familiar and domestic and turning it enigmatic, profound and transcendent. The dialectics that Yamamoto proposes between light and the objects, no matter how simple and familiar they may be, illustrates the beautiful aphorism by George Braque: “mystery blazes forth in broad daylight; the mysterious blends with the darkness.”

Points of view

The above-mentioned image with a soccer goal is a landscape with a rectilinear horizon, dividing the regular plane of the photo into two overlaid planes, one dark, the ground, the other, a little larger and bright, the sky. It is a simple, stark landscape without any features except for the goal post located right in the middle, whose crossbar strictly coincides with the horizon line. This information is enough for us to identify it as a partial view of a soccer field which lies – one can’t tell for sure – either to the right or left. This detail is irrelevant, since what attracts our attention is the distortion imposed on the side posts of the goal. Despite that the crossbar is level with the ground, a certainty which is confirmed by its strict correspondence with the straight border of the landscape, the vertical posts are very dissimilar, the left one being much taller than the right one. This sort of distortion would not take place if the photographer had limited the angles of view to those that are possible when the photographer is standing on the ground, but is explicable if you imagine that he climbed up on something, for example, a ladder, with the purpose of creating a coincidence.

A little left of the center of another photo with a vertical format and the sepia tone typical of those kept in old albums – an affect accentuated by the slightly torn edge and by a sort of thin framing formed by the borders of the photo – sits a black cat. Its black and velvety silhouette is surrounded by vague, sparse blossoms and the side of a rock. The cat’s black tail stretches out from the right side of its curvilinear, pear-shaped body. Between its erect ears, crowning its impassible and silent presence, blaze the almond-shaped lanterns of its little eyes. The cat is on the ground, while the photographer is higher up, looking down at it, from the same position from which we are observing the photo – the place where the photographer obliges us to be. By the vantage point – looking at the cat from above and thus making it appear small – Yamamoto reiterates: the cat’s majesty lies in its pose; while all its mystery lies in its demeanor, its color and its lights.

Another photo has a horizontal format like a landscape, yet its entire left side, captured at point-blank range and contrasting with the light cream tone of the rest of the image by its hues that tend toward black, bears part of the profile of a face with closed eyes and a half-opened mouth. The sphericity of the eyelids evinces the oriental background of the person portrayed, a roundness enounced by the luminosity that is smoothly scattered on the silky skin, without wrinkles or folds, chiseling, besides the eyes, the cheek, the lobe of the nostril, echoing in the tiny visible portion of the upper row of teeth, the curve below the lower lip, the passage of the chin to the neck. The sinuous design of the profile, sketched by the light, is interrupted by the photo’s rectangular format, which crops the figure. The dark face next to a plane whose pallid color, speckled by small points, caresses it. Is the half-open mouth exhaling? Inhaling? How can we know? The certain thing is that, absorbing or receiving the impact of the light, the luminosity makes a face appear within the shadow, which pulls it into its interior.

Correcting what was written above, Masao Yamamoto’s work does not only concern familiar beings, objects and situations. It also concerns the relation between them, the intricate relation between them and the light, between them and the formats chosen for the photos, between them and their relation with the photographer’s disquieting, changing, startling points of view.

Agnaldo Farias / critic and curator / Professor at FAUUSP